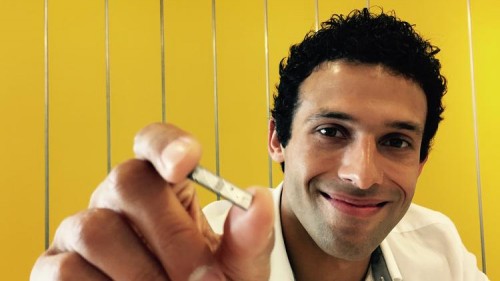

54% of the life science companies (including MIT spinout SQZ Biotech, pictured above), launched at the VDC were founded by foreign-born entrepreneurs that came to Massachusetts for graduate study and remained to launch a company. The Massachusetts Global Entrepreneur-in-Residence Program has increased their odds of getting a visa from less than 50% to 100%!

The Venture Development Center, more commonly referred to as the “VDC” at University of Massachusetts in Boston, is an experienced community guiding startup companies from vision to launch, no strings attached. Ninety-five entrepreneurs, both from life science and technology, are currently in residence. About one-third are from UMass, while the rest are from Harvard, MIT and other universities.

It is truly a special place. Not a day goes by without learning something new from an entrepreneur. That’s because the entire VDC staff spends a lot of time listening. Listening with the goal of understanding is the key to being helpful to entrepreneurs. It’s also the precursor to discovering new opportunities to help many entrepreneurs.

Only by listening can you link together pieces of information to reveal bigger ideas to make the business ecosystem more supportive. My experience in business, university and government helps me to see connections. But it is our willingness to experiment that allows the VDC to then integrate them into something that never existed before.

Great teams are looking for an opportunity to startup

This is how the VDC came into being in 2009. (I’m Assistant Vice Provost for Research at UMass Boston, and the Founder and Director of the VDC.) We knew the city had been awash in NIH grants for decades and could see the shifting emphasis on translation (commercializing research) versus discovery. Our own university was growing in life science. Other tech transfer officers confirmed the shortage of lab space suitable for founders ready to take the tactical step from their university labs to environments where they could prove out the technology by generating the data needed to raise financing. Small, reasonable priced and well-located facilities would be a draw, despite being outside the traditional hub Kendall Square. At the end of the day scientist entrepreneurs will always choose the best value for deployment of their scarce capital.

The bargain with UMass was that I could have 18,000 square feet of hotly contested space (a former cafeteria) in the heart of the campus if our team raised the money to build startup labs and offices externally, and be financially self-sufficient. This would also serve as an example for others on campus to be more entrepreneurial. We started in 2006, and successfully raised $7.8M from five different sources to build the VDC.

We opened the VDC in 2009 at the height of the global financial crisis, when investors had taken a walk on biotech, making it challenging for new companies to get financed. However, it was still apparent that there were great teams looking for an opportunity to start. The VDC started small with only four labs and launched 13 venture backed biotech startups that eventually raised over $130M. Three months ago, one of our companies, SQZ announced a $500M deal with Roche to fight cancer with novel cell engineering technology.

Focus on global entrepreneurs

This same dedication to listening how to make the ecosystem more supportive of entrepreneurs led the VDC to jump into Massachusetts’ pioneering Global EIR Program when leaders at other universities wouldn’t.

I got a call in 2013 from Pam Goldberg of the Mass Tech Collaborative who asked if I’d join a group of heavy hitters who had been working on Mass Passport, a strategy to help startup founders get visas so they could stay after they graduate and launch their business.

Why did I eagerly volunteer to pilot and now lead the program? Because the VDC attracts science and engineering focused entrepreneurs, I had come in contact with many who came from abroad to study at our universities. 54% of the 13 life science companies (including SQZ) launched at the VDC were founded by foreign-born entrepreneurs who came to Massachusetts for graduate study and remained to launch a company. They all talked about their immigration woes.

I also understood that my own university was globalizing. Many of our students are first generation and have modest means, unable to afford to study abroad. Surrounding them with global entrepreneurs would give them a great experience, and maybe even a great job.

For their sake, I understood how vital it is for Massachusetts to win the global war for talent. A conversation years earlier, in 2010, with Iker Marcaide helped me to connect the dots. Iker graduated the previous year from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology – Sloan School of Management. He told me about his startup, peerTransfer, which helps universities streamline the processing of international tuition payments. But would UMass be willing to try the service out for itself and would any students be interested in joining the peerTransfer team?

Marcaide, a Spanish national, started the firm after being shocked by the cost of wiring fee payments from abroad. peerTransfer is solving a problem most don’t realize is a problem: it’s difficult and expensive for international college students to transfer money to pay their tuition. 55,447 currently attend a Massachusetts university, 8.2% more than in 2014.

Now called Flywire, the Boston-based company has raised $43M in venture capital, and last year doubled its revenues and headcount to 98.

Iker ended up hiring Catherine Cam, a Newton North High School grad and UMass Boston economics major. Cam worked at peerTransfer for 13 months as a Sales Operations & Marketing Intern while she completed her studies. She’s now an applications developer at Granite Communications.

Iker opened my eyes to the thousands of business, science, and engineering graduate students who attend a university in Massachusetts on an F-1 visa and desire to remain to grow a company. I also learned that Iker is a lucky one. The odds of international students like him obtaining an H-1B work visa in the national lottery after graduating are less than 50%. It is so challenging for startup founders to simply qualify that many don’t even try.

Reversing the exodus of Massachusetts most entrepreneurial grads

After the idea of an entrepreneur startup visa died in Washington, D.C., the Mass Passport group was formed. Massachusetts wanted to take matters into its own hands and increase the odds for grads like Iker. But they needed a university to step forward to use its cap-exempt status (allowing an entrepreneur to bypass the national H-1B lottery and get a cap-exempt visa) to make the program work. UMass was the only university willing to lead.

The Senate and House staff who worked on the bill to provide money for what is now known as the known as the Massachusetts Global Entrepreneur-in-Residence Program (GEIR) had no problem with engaging in regulatory competition with the feds, but wanted answers to convince their members why this was good for the state. Shouldn’t we be helping our own native born entrepreneurs? I drew on plenty of stories foreign-born entrepreneurs had told me, and pointed to what job creating machines their startups were.

Greg Bialecki, Massachusetts Secretary of Housing and Economic Development, understood the need for more evidence, as a result the VDC received funds from the Mass Tech Collaborative to pilot the program with two entrepreneurs.

Jeff Bussgang, a Flybridge partner, and the driver behind the GEIR idea, told me, we’d better find a way to add more entrepreneurs. Two entrepreneurs prove little. Even though they were his students from Harvard Business School, statistics say their companies might not survive, even though in failure, they’d become better entrepreneurs. This is a hits based business, and depends on lots and lots of trips to the plate.

So, through scrappy experimentation, Jeff and I figured out how to add more entrepreneurs without any more state money. Good thing, because the state had a budget deficit, and couldn’t make good on its $3M promise.

Last week, GEIR reached a milestone – its 10th visa. What this means is that GEIR has increased the odds of entrepreneurs graduating from our universities getting a work visa from less than 50% to 100%!

It took all of 2015 to get these 10 visas. I’ve probably spent 25% of my time on it. Each visa involves a laborious, 22 step, three-month process involving as many as nine administrators at UMass. The way the university has rallied around GEIR is impressive.

The total venture capital raised by the 10 entrepreneurs’ nine companies is $49.9M. The companies have a headcount of 137 employees. We are in process of doubling the number of entrepreneurs in 2016, with 13 already accepted. The next challenge is how to support hundreds more who want to remain after they graduate and grow a business. I think it is time other universities follow our lead.

Making the ecosystem stronger is everyone’s mission

GEIR has been transformative for the entrepreneurs and hopefully Massachusetts. We’ve written the playbook how to reverse the exodus of a group of our most important grads. Founders in California have even moved back to participate in the program!

I am proud that UMass has stepped up to the plate to make our ecosystem stronger. After all, that’s its mission as a public university.

But it should be everyone’s mission. So, let’s stop boasting about Massachusetts being the most innovative state, and instead listen more carefully how to make it the best in the world for global entrepreneurs.